Fashion needs a reality check. A shiny veneer means nothing if there’s no substance behind it. For something to be truly stylish—to stand the test of time, to deserve a spot in your wardrobe—it needs that can’t-quite-put-my-finger-on-it element that takes the dependable and turns it into the undeniable. It might be the history, or a single detail. It might just be a feeling. Regardless, it says the same thing: This is it. This is the real deal. In an era when brands flare into and out of existence in a snap, when the trend cycle is spinning like a teacup, that kind of authenticity isn’t just valuable; it’s vital. ¶ On the following 31 pages, we’re highlighting the people, items, brands, and ideas that exemplify genuine, no-bullshit style and show the way forward. We’re calling them the New Authentics. And whether they’re new or old, big or small, every one of them has that extra something that makes them feel real—and really damn good.

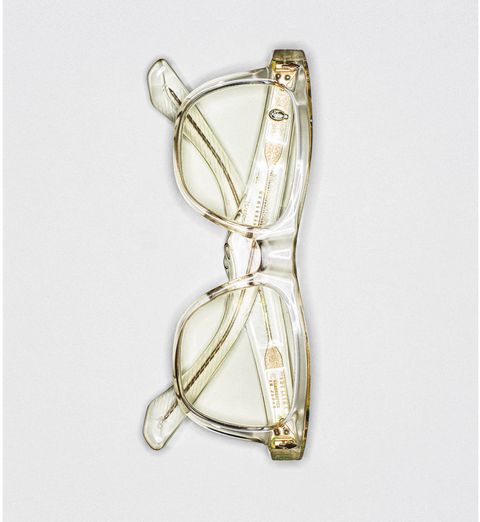

There’s something about a pair of Jacques Marie Mage glasses that invites hyperbole. Substantial or weighty describes the thick acetate frame of the Dealan or the Molino, but they don’t quite cut it. Bulletproof feels better. These things are tough. JMM fans know it. That’s why they’re buying up every small-batch wayfarer and cat-eye—no more than five hundred pairs of any given style are made—from the independent brand founded in 2015 in L. A. by French transplant Jerome Mage, even with prices that’ll raise your eyebrows above your aviators. It’s not just the impeccable Japanese construction or the balance of Old World charm and new-school design. It’s the feeling of putting on those big, bold glasses and recalibrating your entire vibe. Suddenly you’re not tired or harried or even excited. Just like your glasses, you’re bulletproof.

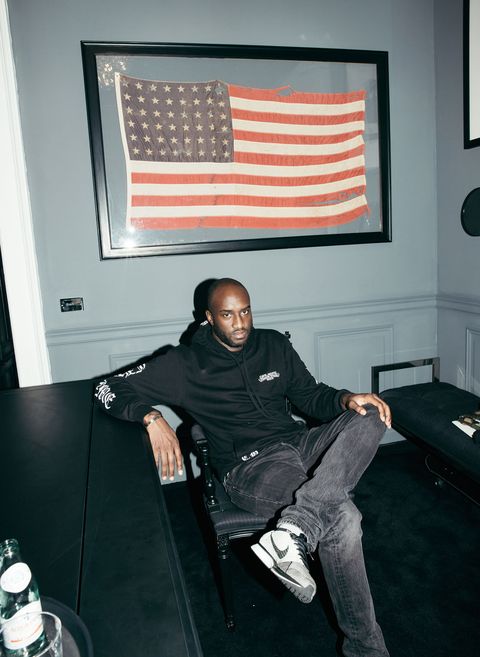

The late Virgil Abloh, the visionary behind Off-White and menswear at Louis Vuitton, once declared, “Everything I do is for the seventeen-year-old version of myself.” Seventeen-year-old me was troubled with fears of a friend finding me perusing the aisles of the St. Vincent de Paul secondhand store—or worse, arriving at school with my clothes redolent of the hand-me-down funk. Virgil founded Off-White in 2013, and truth be told, I was a skeptic, and was still one when the first Off-White Nike collaboration dropped in 2017. But what I see more clearly now is how much Virgil’s story—the Rockford, Illinois, roots; the Ghanaian-immigrant parents; the bachelor’s in civil engineering; the master’s in architecture; the creative direction for Kanye—imbued his brand with value, how me buying Off-White and other luxe-priced clothing has been a way to beat back those old anxieties, has become something approaching an antidote. Not as ostentatious as a boulder-sized diamond stud, but a symbol to my damn self that I will never again wear anything that makes me feel poor.

Mitchell S. Jackson is a novelist, Pulitzer Prize winner, and contributing writer to Esquire.

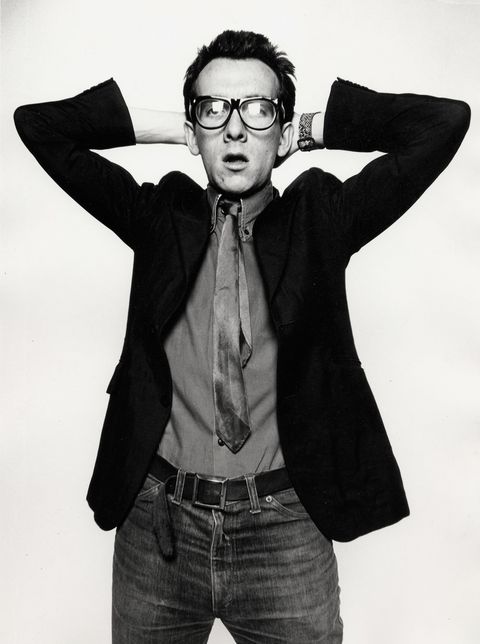

The coat and tie were once a signal for white-collared desk warriors that they’re working, not playing. But the tie’s popularity as part of a uniform has been declining for at least a decade. Mad Men gave it a brief renaissance, before the pandemic and work-from-anywhere all but killed it. As it recedes from most areas of American life, the tie has come to signal something new. It’s a statement of, if not subversiveness, at least a willingness to stand apart from the pack. Because if you want to wear a tie well, you have to be willing to put in the effort. Think of it as an opportunity to embrace formality and celebrate the good times, or simply to feel good.

Wear one with a suit. Or separates. Or even jeans. For inspiration, look to Jean-Michel Basquiat, Elvis Costello, and Patti Smith, who didn’t need to wear a tie. They chose to–and it made them look cool as hell. “Serious ties” are made from printed silks decorated with stripes or small, repeating geometric patterns known as foulards. For something a little more casual, try cashmere or wool challis in the fall and winter and linen or raw silk in the spring and summer. The most casual tie is the floppy silk knit. Get one in black and wear it with nearly every coat your imagination can conjure. Even on the weekend, and especially when it’s not required.

Derek Guy has written about men’s style for eleven years.

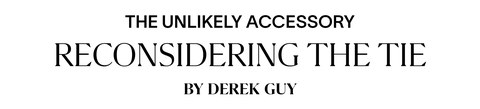

Good denim all starts with tailoring. That’s why my background helps me; I’m originally trained as a bespoke tailor. You learn that you have to follow these rules to make a proper garment. You learn how important the craftsmanship is, about the work behind the product.

The design of a jean is so classic that if you try to redesign it too much, it takes away from that tradition. It won’t look as authentic. The philosophy of Glenn’s Denim is just: Make a beautiful product using the best- quality materials that are available. Really well-made denim becomes a part of you. That’s the beautiful thing: It learns your body. It shapes to your body. These jeans become unique to your own person—how you sit, how you walk, what your stride is. Our brand was founded in NYC very much inspired by an old-school, underground subculture that wore denim—artists, musicians, writers, painters. I look back to the seventies and eighties, the artists and the underground movement of hip-hop artists and musicians. Run-DMC started wearing raw jeans as part of hip-hop culture. There were artists wearing denim in SoHo. It transcended into this beautiful fabric. First you see it as workwear. You see it in old western cowboy movies. Then you see Marlon Brando in denim and you think: How cool does he look in jeans? I saw denim in the movies before I ever saw the fabric in real life, and I fell in love with it once I did.

Denim is the world’s uniform, and people relate to it instantly. It’s almost like music. You hear music and you might not know the words, but once you can hear the rhythm, you can move to it.

This article appeared in the March 2022 issue of Esquire

subscribe

You will only notice a missing button or unraveling hem the moment you are about to leave the house. This is a law of the universe. And that means unless you can fix it yourself, you will go buttonless to the ball. So learn to mend it. Yes, with a needle and thread. We’re not talking about studying for a master’s in sock darning. Basic skills are all that’s required to maintain your wardrobe. And the more you do it, the better looking—and more lasting—your fixes will be.

As with repairing an engine, a few of the right tools are all you need. Buy good thread in the colors of your clothes, a pack of needles, some fine scissors, and a seam ripper. Get into the habit of saving buttons, especially the spare ones that often come in a little envelope in a new jacket. Don’t be above sending things out for complicated procedures. And use hotel sewing kits only when absolutely necessary. Your wardrobe—and wallet—will thank you.

While most modern tech jackets are destined to look meh in a few years, a waxed-cotton Barbour looks its best after putting on some miles. You could wait decades for your new International to weather itself into a pleasing state of decrepitude. Or you could, like me, cheat and buy one to which someone else—possibly several people—has already done the hard work. Its story will be written in each crease and stain. And the worse it has been treated, the better.

Such is the currency for these old Barbours that often, for a really well-aged piece, you’ll pay more than the cost of a new one. If you care about the style, the price won’t bother you. A handy way to date a prospective purchase is to look at the label inside. Barbour has received three royal warrants to supply clothing for shooting, fishing, and other outdoorsy pursuits by the British royal family. They date from 1974, the first, from the Duke of Edinburgh; 1982, from the Queen; and one last one, in 1987, from the Prince of Wales, aka Charles. Modern Barbours carry all three. For some, this adds cachet. But it’s the ones predating the early seventies–with no royal warrants–that get hardcore collectors all hot and bothered. Prices skyrocket. So it pays to keep hunting, on places like Etsy and eBay; occasionally a real gem will slip through the clutches of the eagle-eyed vintage dealers and make it direct to you—for a song—from its original owner.

The Levi’s Type III Trucker is the standard by which every denim jacket is judged. At fifty-five years old–it was introduced as the Lot No. 70505 denim jacket in 1967–its authenticity is undisputed. This one, thoroughly thrashed and lovingly worn to (almost) pieces, is part of the Levi’s Authorized Vintage program, wherein the folks with the little red tag reclaim throwback items and offer them back to the buying public—after a little cleanup, that is.

But even after getting some TLC, a jacket like this bears the marks of its former life. And all those rips and tears and repairs show us how good the right piece of clothing can become when it’s been put through the wringer. It approaches exhaustion but somehow never gets there, and it becomes more transcendent along the way. Fashion has for too long been trapped in a “use it and lose it” cycle of hypernewness that’s more than worn out its welcome. A battered trucker jacket is proof that good things come to those who step off the hamster wheel, even if—perhaps especially if—a prior owner has made it easy by putting in all the hard work for you. (For more on that, just check out the opposite page.) It’s both a beacon of what lies ahead and a bit of necessary inspiration to stay on the path that’ll take you there.

The jumpsuit is the black tie of casualwear—this is the knowledge I bring you.

As one who gets up early and must creep out of bed without awakening a grumpy sleeper, I had to learn to dress without thumping blindly in the closet. At first I tried neatly laying out my clothes; it felt like a shift at Old Navy. Then a friend’s teenager gave me his old Dickies jumpsuit—and I fell in love. I could wake in darkness, slip into my Dickies, and bang! Ready for the day! My friend Bart wears a jumpsuit every day. He says it communicates boldness and freedom, even when he does not feel that way; in his words, it “transposes will with circumstance.” I now own a white-striped jumpsuit for dressier days and a gray linen jumpsuit for summer, and, for his birthday, my partner received a custom-made jumpsuit from Etsy’s BoerlinBoerds. I gave one to a lesbian friend and it’s getting her dates. I even bought a white onesie (above) that, with layering, has gone from children’s picnic to formal dinner. Like a tuxedo, it is armor against any eventuality.

“To those who are thinking, I couldn’t pull this off,” Bart advises, “you only can if you try.”

Andrew Sean Greer is a Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist and short-story writer.

Growing up, I had to go to church every weekend. And the uniform for church was a pair of khakis, a white shirt, and penny loafers. The loafers—and the whole outfit, really—have never left my wardrobe.

People always describe a penny loafer as a “dress shoe.” That’s not the way that I wear it or see it. I wanted the loafer to feel sort of like the Air Force 1, which is a great base product in the sense that you can play with it as much as you want. There are hundreds—maybe thousands—of colors of Air Force 1’s. My goal from the beginning was to make a great base product out of this loafer. I wanted something heavy, something that has some substantial feel to it and a lot of curb appeal at the bottom of your pants. I also put this New Yorker sensibility into it because I wanted them to feel like you can’t bust them, no matter how much you walk in them. There’s the reassurance there that you are getting something that is of quality.

It’s not about just a loafer and having a hot moment, though. Fuck that. I’m a designer first and foremost. Blackstock & Weber is not a shoe company. Blackstock & Weber is a house of perspective, and this perspective isn’t one product. It’s not singular in any sense. There will be apparel. There will be accessories. There are different ways for me to tell this story.

I want to be the voice. Before, it was Ralph. Tommy had his time. That’s what American menswear was and felt like. But now, luckily, we’re at a place in history where it’s not weird that that person is Black.

I’m trained as an archaeologist, and that’s how I work in the world. The clothes I make are archaeological, anthropological. They come from somewhere else to say something here.

Even the brand Rowing Blazers was born from a book I wrote on the history of blazers people wore to regattas. If you’re not rowing, you’re in a blazer—but not just any blazer. It’s going to have certain colors, certain details, that match the club you row for. It’s about heraldry, about symbols, about the tradition and rituals and myths that make up the history of a club. I remember seeing the blazers at the Henley Royal Regatta in England and I thought, Someone should write a book about this. I became that person—and then I started making those blazers. We make much more than that now, but I’m still just bringing things into the world that I wish existed, some of which used to exist. I knew I wanted to do rugby shirts early on, for example, but I had to fight to get them to look and feel as though they were OGs: soft, heavyweight, with a spread collar. I had to convince manufacturers to develop that collar. “Says who? You’re just some guy who studied archaeology.” In their defense, we hadn’t made anything yet. Now we make and sell a lot of rugbies.

Authenticity and my own passions guide what we do. I think about our dad hats with the logo from Harry’s New York Bar in Paris, one of my favorite places in the world. It’s the birthplace of the Bloody Mary, the sidecar. When you see that little logo, it means something. There’s substance, there’s depth to it. It’s a signifier of something beyond itself.

Whatever it is we do, it all comes from a simple idea: Someone should do this. Actually, I think we should do this.

There was an era in humanity when people wrote letters, and then an era when people were obsessed with TV, and that became the best way to get the message across. Right now, people are obsessed with clothing. To get across what I’m thinking so that others can see it, so that others can feel it, it’s through clothes.

If you’re coming to the village of Denim Tears, you’ll see my graphics are my totems. They say: This is the birth of America. This is the pain. This is what needs to be reconciled. That’s something the Tyson Beckford sweater seeks to do: to render the white gaze emitting from the American flag powerless, for at least a moment. For a moment, to give ownership over that flag to African Americans, casting it in the image of the people it has oppressed and struggled to represent from its beginning until today. Or images like Black Jesus in a cotton-wreath crown. The image is a big part of American iconography, how the slave owners colonized Africa and brought people to America through the placating of religion. It had you praying to a god that doesn’t look like you. I give you the same features you’re used to but Black-washed. That’s the irony: The white version of him helped you pick that cotton. That’s how they kept you placated. How does it feel to tear that down, from the inside out? I want to rip that ideal, that image, that brainwashing.

What I do at Denim Tears, what I’m always doing, is expressing the human condition. Clothes are one medium, but there are others. Ceramics, film, short film, music. All of that is about the human condition. At their core, they’re about what it means to be human. What’s important, regardless of medium, is to make something that you think expresses life.

These were the first adult shoes I purchased. They’ve got to be fifteen years old. I’d won an award and I was like, “Fuck, I gotta show up.” So I went and bought them. But true to myself, I wore them like Vans. No socks. Never. The one time in my life I wore them with a proper suit was for that event, and even then I didn’t wear socks. That’s why the tape is on the bottom—because I wore through them from sweat and just having at it. But they’re tough. Investing in your style is about things being bulletproof. Every summer, I buy a pair of Vans and they get destroyed. These shoes are still going. And now they’re almost like military-chic moccasins. I wear them with fucked-up denim. A big cuff. There you go.

That said, a pair of Church’s will work in any wardrobe you want to force them into. So clean up, wear them with a suit. If you want to wear a sock, go for it. For me, style should be infinitely flexible, and it shouldn’t be this sort of adornment. It should just be effortless and then, boom. That’s it. You’re in it.

Rockwell Harwood is Esquire’s design director.

When you think of shoemaking—the old-school sort, rooted in skilled craftsmanship and resulting in boots and derbies you’ll wear for years to come—you probably think of spots like England and Italy. And those places are well worthy of their fame and acclaim. But the old guard isn’t the be-all, end-all. Look to locations like Portugal, which has become a hotbed of footwear production in recent years. Or look even further south, then take a big jag westward. You’ll wind up in Léon, Mexico, home to a four-hundred-year shoemaking history that hasn’t always gotten the recognition it deserves. No longer. In search of well-made footwear that’s still relatively affordable—in the $200-ish range, as opposed to $500-plus English or Italian options—a new breed of upstart, often direct-to-consumer brands has turned to Léon to make everything from rugged cowboy boots to polished oxfords. Those brands, like Tecovas and Thursday Boot Company, aren’t shy about it, either. So take a closer look and see where the shoes you just bought came from. If it’s Léon, you can rest assured that they were in very capable hands before they landed in your own.

There are serious advantages to building a uniform. It’s easier to get dressed in the morning. Packing is a breeze. You feel prepared for whatever the day throws at you. But the real edge is the thrill of exploring outside of it. And now, as we’re reworking our wardrobes after years of Instagram- fueled excess followed by crushing casualness, there’s much exploring to be done. Which means that really nailing your starting point—establishing a strong baseline—is crucial.

I adopted my own uniform twenty-five years ago. I like a dark color palette. Black, navy, and gray. It sounds basic, but when you consider fabric and texture—a tweed or flannel sport coat, a merino or cashmere sweater, a cotton gabardine or linen pant— you’re able to craft something with real depth. From there, experimenting is easy. You can bring in new colors, patterns, and accessories without worrying about going off the rails. Try a bold plaid under that flannel sport coat. Pair a bright sweater with those gabardine trousers. Bust out some wild sneakers and trust that, thanks to your carefully considered, understated outfit, they’ll look intentional, not try-hard. And remember that a standout watch really shines alongside a sharp, simple look. Your formula might wind up entirely different from mine. Maybe you’re big on neutrals, or military- inspired clothing. It’s not about what the uniform is; it’s about finding one at all. Once you do, you can figure out how to evolve it, how to make it even more your own. And that’s when things get really interesting.

Ted Stafford is Esquire’s market director.

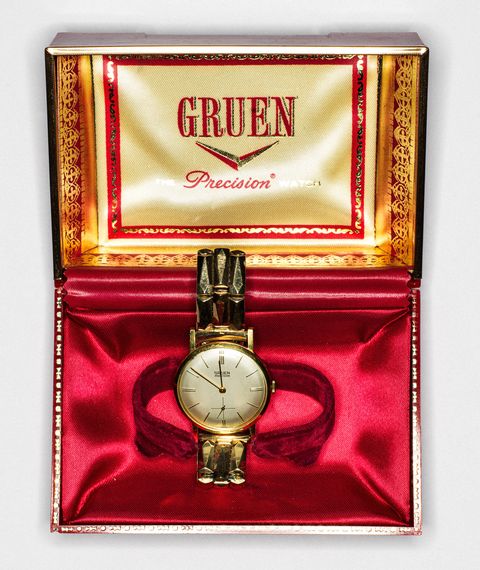

JAMES BOND MAY be British to the bone, but the first watch he wore onscreen was an American. Tucked under the cuff of his tux in 1962’s Dr. No is a timepiece from a brand called Gruen.

Founded in 1894 by German immigrant Dietrich Gruen and his son Frederick, the Cincinnati-based watch company was one of the largest in the States before it was sold for parts in 1958. So how did a Gruen Precision wind up on Sean Connery’s wrist years later? According to 007 legend, it was his own watch. True or not, it’s a good story. Gruens seemed destined for the proverbial dustbin until eagle-eyed fans ID’d the brand on the OG Bond, sparking a resurgence in notoriety. The timing couldn’t be better. Gruen’s dressed-up, midcentury vibe wasn’t just a perfect complement to Bond’s razor-sharp style in ’62—it also happens to be where watches are going in 2022. Ditto for other designs from the Gruen archives, like the deco-inflected Curvex, with its long rectangular case that follows the curvature of the wearer’s wrist.

The modern fascination with tough tool watches (like Bond’s famous Rolex Submariner, also from Dr. No) isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. But as fashion’s pendulum swings, guys are also gravitating toward stuff with more snazz and refinement. And unlike other once-underappreciated midcentury gems—think Universal Genève a decade ago—Gruen hasn’t been sniffed out and bid up to extreme prices by collectors. Yet. The enterprising individual, willing to do a bit of sleuthing, could very well get in on the ground floor with a brand that’s poised for a come-up. It’s not quite spycraft, but it seems a safe bet that Bond would approve.

I WAS BORN and raised in Toledo, Ohio. Small town, but it does a lot of amazing things. When I came home from college, I was working as a conductor engineer for Norfolk Southern railroad. On my days off, I helped a friend run a streetwear boutique. That birthed my love of fashion. I started styling my friends, then local rappers, then Machine Gun Kelly. Years later, after moving to New York, his stylist at the time connected me with Kanye West around the launch of The Life of Pablo. I worked with him for four and a half years, and we ended on really good terms. It was a dope time to, as I say, “go to Ye University.”

Shortly after that, I launched my own two brands: Midwest Kids, which is more streetwear based, and my namesake brand, which is more workwear inspired. Both brands are inspired by my parents, Midwest Kids being after my mother—the athletic, cozy, leisure vibe—then Darryl Brown being named after my dad, because one, I am a Junior, and two, my dad is just super workwear oriented. Worked at Chrysler for thirty-plus years. Wears boots every day. I said, coming into this, I wanted to have my own Carhartt. I wanted to have my own Champion. Midwest Kids is my own Champion-type brand. And then Darryl Brown is my own Carhartt- type brand. I don’t necessarily want to be better than them or compete with them. I just want a seat at the table. I want people to one day be like, “Ben Davis, Dickies, Carhartt, Darryl Brown.” And it’s just not a thing. It just rolls off their tongue.

As of January of 2021, I relocated back to Ohio and bought a building downtown. I made that my headquarters and my studio—my fantasy factory, I guess you could say. And I’m just using my platform to help other creatives in the Midwest and continue to grow. I feel like I’m a storyteller. I just use clothing. I use garments to tell my story.