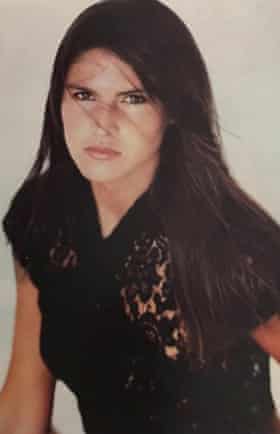

In the autumn of 1985, 22-year-old Marianne Shine was invited to Paris to try her hand at modelling. A confident and academic young woman, she had graduated in classical art and archaeology from her college in Pennsylvania, having spent several summers in Greece on archaeological digs, and was excited to visit Europe again. Her Danish mother, a travel agent, and Hungarian father, a gynaecologist, encouraged her to go, convinced that the modelling agents there would take good care of her.

But after six months of modelling in Paris, Shine returned home a different person. “Before Paris I was this playful, creative girl, but that part of me vanished,” she tells me now. Her mother found her a job at a travel agency in their suburb of New York, but Shine wasn’t interested. She says: “It was like this deadening. I couldn’t fall asleep at night, and then I couldn’t wake up in the morning. I could barely trudge through the day.”

What Shine knows now but didn’t have the words for at the time is that she was experiencing a “deep, deep depression”. In Paris she had been sexually assaulted multiple times by men in the fashion industry. This culminated in being raped by her agent, Jean-Luc Brunel, then one of the most powerful men in the business, and the person entrusted with her care.

“I didn’t understand how deeply it affected me and I blamed myself,” says Shine, now 58, from her home in Mill Valley, California. “I felt like this dirty, vile, horrible thing.” She didn’t tell anyone, not even the therapist her mother arranged for her to see. “I just kept burying it,” she says. “I was so alone in that darkness.”

Three decades later, as #MeToo reverberated around the world, Shine opened up to close friends and relatives, but rarely went into details. In October 2020, though, she read the Guardian’s investigations into abuse in the fashion industry, drawing on accounts from former models who had had similar experiences in Paris in the 80s and 90s, including some with allegations against her alleged rapist, Brunel. “I thought: how many other women out there, like me, had buried it?”

Two months later, Brunel was arrested on suspicion of trafficking and raping underage girls. The investigation was being led by police investigating the paedophile Jeffrey Epstein. It emerged that the pair had been close associates, and that Brunel was accused of supplying more than 1,000 girls and young women for Epstein to have sex with. “That blew my mind,” Shine says. “I had no idea what I had been a part of.”

Shine is speaking now for the first time, and has contributed to a three-part Sky documentary to be broadcast next month. The series was developed from my Guardian investigations into sexual abuse in the fashion industry, and follows former models and whistleblowers. In the final episode, Shine is filmed recounting her experiences over the phone to a lawyer in France as a witness in the growing criminal case against Brunel.

On 19 February this year, though, as justice seemed within reach, news broke that Brunel had killed himself in prison – mirroring the fate of Epstein. The 75-year-old had spent 14 months in custody, awaiting trial on charges of rape of minors and sexual harassment, which he denied, along with any participation in Epstein’s sex-trafficking. Shine says she felt “this whole rollercoaster of emotions. I had buried it for so many years and then to have it just go ‘pfft – not possible’ … it was crushing.”

For Shine and the five other Brunel accusers who spoke to me for this story – four of whom are sharing their experiences for the first time – his death has been a trigger to speak out. All say their careers were affected by what they allege took place in Paris. They say Brunel was at the heart of a network of sexual abuse in the industry that still needs to be exposed. There were others around him, they claim, who enabled the abuse and continued to put models in danger, even after allegations against Brunel were aired on US TV in the late 80s. Some of these people continue to work in the industry today.

Shine says: “I don’t have to wait for a courtroom to tell me whether I’m right or wrong. I know my truth. If I don’t give voice to this, it’s going to continue to happen.”

Born into an upper-middle-class family in Paris in 1946, Brunel started his career in restaurant PR before moving into fashion. He rose to prominence as a model scout in the late 1970s, and became the head of Karin Models in Paris in 1978; claiming to have launched the careers of some of the most successful supermodels of the era, including Helena Christensen.

By the 80s, Brunel was one of the leading model agents in Paris and a fixture on the social scene, particularly at the exclusive Les Bains Douches nightclub, where he had his own table. He surrounded himself with VIPs, from businessmen and princes to pop stars and movie producers – and, of course, scores of young models. Nights of dancing were preceded by dinners at his apartment near the Karin headquarters on the elegant Avenue Hoche, or followed by parties there. He’d always select a handful of his favourite models to keep him and his male friends company. Brunel was said to provide bowls of cocaine and encourage his guests, models included, to indulge.

A succession of young women who worked for Karin lived in his apartment – often sharing bedrooms. In 1982, Scottish model Lynn Wales was one of them. She describes witnessing one party at his home, which became “more like an orgy”. Brunel’s apartment, she says, “was on one of the big avenues near the Arc de Triomphe. He had a maid and a cook. It was all so foreign to me.” Speaking on the phone from her home in Cumbernauld, North Lanarkshire, she says: “I was like the weirdo in those days, I didn’t drink or smoke. I was sewing a patchwork quilt … they thought I was from Mars.”

One night at Brunel’s apartment, Wales says, he told her to answer his phone. “It was an American mother worried about her 14-year-old daughter who was coming to Paris,” she says. Shortly afterwards, this girl and several others from the US arrived. Wales says she heard Brunel tell the young women he would get them lucrative jobs, including a Benetton campaign and several pages in Vogue. Soon, they joined Brunel’s party, which she says was “filled with old, fat men”.

“My room was down the hall from the salon, which was where it was going on … and what I saw that night was horrific,” says Wales, who was 17 at the time. “These poor girls were just kids, and there were piles of cocaine. It was like a Renaissance painting: underwear, nudity, cocaine … definitely sex going on.” Wales, now in her 50s, adds: “I just went into my room. I was shocked at what I saw and I suppose a bit scared.” The next day, she says, she confronted Brunel and they had “a big fight”. Soon afterwards, she left the agency and returned to London, disheartened.

Four decades later, on 20 December 2020, after learning of Brunel’s arrest, Wales, who runs a cleaning business in Glasgow, reported what she had witnessed to Cumbernauld police station. “I’m from a wee village in Scotland … they must have thought I was mad,” she says.

In the 1980s, many of those trying to make it at agencies in Paris were teenagers from the US, Canada or elsewhere in Europe. Most were away from home for the first time. For Marianne Shine, it was less a long‑term career move and more a way to make some money and travel before returning to her studies. She was comfortable in front of the camera and spoke a bit of French. “I thought I had it together: I have a college degree and I’ve travelled, and my parents are European,” she says.

However, in January 1986, within weeks of arriving in Paris to work for Prestige – a French agency run by Claude Haddad, one of Brunel’s biggest rivals – she was beginning to feel out of her depth. Haddad was another power player, who had discovered Jerry Hall and Grace Jones. His staff were sending Shine all over Paris for castings, but she had limited success. She began witnessing her boss’s predatory behaviour towards young models and was disgusted when one day the same thing happened to her. Haddad (who died in 2009) called her into his office in front of clients and other agency staff and sexually assaulted her, she says. He pulled her shirt down to show her breasts, “hoisted up my skirt, smacked me on the arse and spun me around,” she says. Shine couldn’t believe that no one did anything to stop it. She left Prestige shortly afterwards to find another agency – somewhere she’d feel safer.

When Shine found herself at Karin’s sunny office near the Champs-Élysées, it felt full of promise. Getting in felt to her “like joining an exclusive club”. When she first met Brunel, he told her she wasn’t allowed in until she slimmed down. “He’d say, ‘You need to lose more weight in your face, come back next week,’” says Shine. After several weeks of extreme dieting, she stopped getting her period and began to lose hope that she would make the cut. But one day Brunel finally told her she was ready.

That night Brunel whisked her off to a Sade concert in a limousine. “I was so excited,” she says. There were other models in the car, but Shine was alone with Brunel in the back seat and “he was sort of interviewing me,” she says. After that, Shine started getting bookings. “Being a model with Karin’s gave us this privilege,” she says. “Where there would be the velvet rope and people queueing up outside, they would just let us in. It felt so cool, like we were celebrities.”

In the spring of 1986, she was invited to a dinner at Brunel’s house: “He had a very nice flat, very fancy.” Several top models from the agency were there, as well as a number of men, including one Shine now believes was Harvey Weinstein. She was keeping an eye on the time, conscious of when the Métro would stop running, but says Brunel kept insisting: “No, no, no – don’t leave yet. We’re just having fun. I’ll have someone give you a ride home.”

When the time came to leave, there was no one to take her home. The other models suggested she stay at the apartment, reassuring her that they slept over all the time, but she wasn’t sure. “Everybody went to bed and Jean-Luc and I sat there, and he was like: ‘Yes, I really have hopes for you.’ I felt privileged. He went: ‘How about I bring you a pillow and a blanket and you sleep here?’” Shine reluctantly agreed. Brunel went to his room and she fell asleep on the couch, but Brunel soon woke her up. “He was wearing a silk robe, he was kneeling next to me, and he was like: ‘Go sleep in my bed.’ He kept repeating that I needed my beauty rest.” Shine repeatedly said no, and he went away. Eventually, she remembers: “He was standing over me and was insistent, almost angry, and he went: ‘Go to my bed, I’ll sleep out here, you go now.’ I stupidly went into his bedroom, into this big bed with these satin sheets.

“Somehow I managed to fall asleep again, and I woke up and he was on top of me,” says Shine. “He was naked and he was thrusting between my legs … ” Shine says he was able to penetrate her through her underwear before she was able to push him off. This, she says, made him angry. “He took my head and tried to make me go down on him.” She was able to resist, but Brunel took her hand and placed it on his penis. “He passed out and then rolled over and slept,” she says. “I was petrified.” As soon as Shine heard his breathing change, she sneaked out. “I was in full-blown survival mode, like: get the fuck away,” she says.

Shine feels most angry about what happened at the agency the following Monday. “I showed up, and my booker was there and she was like: ‘I can’t be seen talking to you … you have to go.’” Shine says she went charging into Brunel’s office. He was on the phone, and repeatedly shouted for her to get out. Shine recalls Brunel saying: “I’m going to call the police on you. You don’t work here any more,” before pushing her out.

“I couldn’t understand it. I was the one who’d been raped.” Reflecting on the incident, she says tearfully: “I really believed him when he said that stuff to me. I don’t think I’m stupid. I think I’m quite intelligent, but a part of me wanted to believe him. Looking back, I think Jean-Luc was grooming me, and if I was someone who would play along with his fantasies, then he’d help me work. And if I was not going to be a player, then he would make sure that I disappeared.”

Shine returned to live with her mother in Bronxville, New York. During the previous six months, she had been repeatedly subjected to sexual harassment and assault, including an attempted rape by a fashion designer who told her that sex was “what models are for”. She says: “I didn’t tell my parents … or anyone.” It became clear that the events in Paris had spelled the end of her modelling career. Her diary at the time reveals a woman battling with her mental health. Her first entry after the Brunel incident, on 12 June 1986, reads: “I hate myself, I just keep crying … I think I’m going insane … this pain of misery is too great to be tolerated any more. I will do something drastic.” She says now that she was suicidal. “I feel so sorry for that young woman that was me.”

Two years later, in December 1988, CBS released a 60 Minutes investigation into abuse in the fashion industry, presented by Diane Sawyer. Titled American Girls in Paris, it revealed allegations against both Haddad and Brunel. Shine and her mother watched from their couch as Sawyer asked Haddad if he had slept with any of his teenage models. He responded: “Almost never.” Brunel declined an interview, but Sawyer talked to several of his accusers, including a woman who spoke anonymously to say he had drugged and raped her. “Boy, did that hit close to home,” says Shine. “I didn’t realise how bad it was. There was this pattern through the entire industry. It wasn’t just me.” She confided in her then boyfriend about what she alleges happened with Brunel, and he has confirmed her account to me. However, she still couldn’t bring herself to tell her mother. “I still felt too much shame,” she says.

After a brief flurry of controversy, the CBS programme was the subject of an undisclosed legal threat. A spokesperson for the TV company said recently that the programme is “still on legal hold”, meaning the recording or even a transcript cannot be shared. Brunel’s career continued to thrive.

The following year, in 1989, Brunel had a hand in creating another agency, Next Management, based in New York, which is still running today. Craig Pyes, who produced the CBS film, says: “We accused somebody of drugging and raping people in front of 8 million people, and then they can come to the US, open a modelling agency and bring in more underage girls? What happened?”

A spokesperson for Next Management says of the allegations against Brunel: “None of that happened in our orbit. When we started Next in 1989 we had no idea about any of that – zero. It was a very short-lived relationship. He left after a year and a half and neither of the partners ever ran into him again.”

In 1995, Brunel expanded Karin into the US. Joey Hunter, a veteran American agent, agreed to go into business with him in New York. “It was the biggest mistake of my life,” says Hunter, who sold his stake and quit after two years, sick of Brunel. Brunel also continued in a senior role at Karin in Paris through the 90s, but stopped working for the Europe division by the end of the decade. Karin continues to be a leading agency in Paris today, but declined to comment for this article.

In a 1995 interview with journalist Michael Gross, who was writing a book on the modelling industry, Brunel claimed there were other French agents whose behaviour was worse than his, including Haddad and Gérald Marie – at the time the European boss of the leading modelling agency Elite – who was previously married to supermodel Linda Evangelista. Marie was one of Brunel’s rivals, but the pair reportedly “exchanged” models between their businesses and frequented the same parties and clubs in Paris. Brunel told Gross on a tape that will be heard for the first time in the new documentary: “[There are] a lot of other ones that you don’t see, that you don’t hear … Gérald is 100 times worse than I am.” Marie has categorically denied all accusations against him.

Pyes says the alleged behaviour of Brunel, Haddad and Marie (who wasn’t referenced in the CBS programme) was an “open secret” three decades ago. He believes it was able to continue because the industry chose to look the other way. “These were normal girls from all over America and no one cared,” he says. “We’re talking about a conveyor belt, not a casting couch. What I want to know is, who else was involved who helped move this along?”

One of the young women Pyes interviewed for the CBS programme was Courtney Soerensen. Then 19, she told film-makers that turning down Brunel’s repeated sexual advances meant her work dried up. Now she says that what really happened in Paris went much further.

From her home in Livermore, California, Soerensen tells me that not only was she repeatedly sexually assaulted by Brunel in the spring of 1988, but she was also “pimped out” to his friends in an orchestrated system of abuse. She tells me this culminated in a meeting with a man Brunel referred to simply as “Jeffy”, supposedly a top movie agent looking for a new young actress. Soerensen, now 53, says it was only recently, after recognising him in TV footage, that she realised this was Jeffrey Epstein.

Soerensen, who began modelling in her home town of Stoneboro, aged 13, describes her teenage self as “your all-round American girl from a small rural Pennsylvania town”. She played in the school band and sang in the church choir. She and her younger brother were raised by their single mother, a teacher. Her mother insisted she attend college at the Art Institute of Pittsburgh, but Soerensen left three months before completing her degree in fashion merchandising to become a model with the agency IMG. A few months later, she says: “I was sent to Paris to fill out my book, get polished and then come back to take New York by storm.”

From the moment she arrived at the apartment she was to share with other models, “everything was highly personalised and very hands-on with Brunel”, she says. “It was all super-glamorous … I got to go to George Michael’s concert and sit and eat dinner with him and Brunel afterwards … all sorts of crazy, beautiful things.” Soon after, Brunel began pestering her for sex and subjecting her to unwanted touching, grabbing her breasts, putting his hand up her dress and rubbing himself against her. On one occasion, she says, he lured her into his bedroom on the pretext of showing her photos of a Miss Universe contestant whose career he’d developed. “He got handsy, then pushed me down on the bed and jumped on top of me,” she says. Soerensen was able to escape Brunel’s advances because she was much bigger than him: “I was quite thin at the time, but I’m 6ft tall and I was raised on a farm and as an athlete.”

Soerensen says Brunel told her she would be rewarded if she went along with his requests. “He said if I was good enough at these sexual things, he could send me to people who could really help build my career.” But Brunel soon “seemed to understand I had no interest in him and proceeded to set me up on ‘appointments’ with his cronies”. From that point, she says, “there was always this expectation that we’d be available to whoever of his playboy friends were there”. She was sometimes paired up with these men by the female bookers at Karin, who she says “would schedule lunches with them”. Brunel also began punishing her, she says. She had grown a “luxurious mane of hair” and one day Brunel sent her to a hairstylist who “chopped it all off, and turned it bright orange”.

The last straw was the so-called “casting call” with Epstein. She says Brunel told her it was for a role in a Hollywood movie, and that “Jeffy” was looking for someone “young, fresh and raw”, who could also bring some maturity to the part. “I was so excited to be picked,” she says. Epstein is not known to have had any genuine connections to Hollywood, but is accused by others of assuming false identities in order to gain access to young models.

The appointment at 6pm on 3 May 1988 was at an apartment just off the Champs-Élysées. Epstein, who was joined by a videographer, told her: “First I need to see that you’re a good kisser and that you’re passionate. This is going to be a movie with a lot of love scenes, romance, so we want to make sure that you have the right body and show us what you’re capable of.” Soerensen expressed her discomfort, telling him she would prefer to do this with an actor and not with him, but went along with it. She says he then suggested moving to the kitchen to film a different “scene”. Epstein told her: “I’ll come up and start kissing you from behind, and then we’ll make out on the floor.” Soerensen says it was when he put his hands on her breasts and up her skirt that she broke away and told him it wasn’t appropriate. She remembers he then tried to hug her and began touching himself. “That’s when I just had to get out of there,” she says. “I remember shaking … the shame and the fury.”

In the days that followed, she made a tearful call to her US agency, IMG Models, begging to come home. Soerensen told her female agent that Brunel was sabotaging her career because she wouldn’t sleep with him and that she was no longer able to make ends meet. She couldn’t bring herself to tell them what happened with Epstein, she says. “I was horrified that they had video of him touching me in that way.” The agency arranged for her to be spirited out of Brunel’s home in the middle of the night by people from another French agency, and she hid for a few days in another apartment. Soon afterwards, she flew home to Stoneboro.

Soerensen says she was staggered to discover that IMG continued sending young models to Brunel in Paris after that. She says this is why she feels it’s important she speaks out now, “because too many people are complicit”. IMG declined to comment for this article.

She says that what happened with Epstein and Brunel “was something I buried pretty deep”. It wasn’t until she saw footage of Epstein as a young man in the 2020 Netflix documentary Filthy Rich that she realised who the supposed film agent had been. “It was the way that he would tap his fingers,” she says. “He would put his arm around you and do that tapping, and to this day I can’t stand for anyone to touch or tap me like that.” Since then, Soerensen has spent a lot of time in therapy.

Brunel and Epstein are thought to have met for the first time in the 1980s through the British socialite and now convicted sex trafficker Ghislaine Maxwell, but their relationship seems to have deepened in the late 1990s. According to flight logs, between 2000 and 2005 Brunel took at least two dozen trips on Epstein’s private jet – the so-called “Lolita Express”. Only a handful of people, including Maxwell, appear more often. In 2005, Brunel transformed Karin’s US division into a new agency called MC2, with financial help from Epstein, opening offices in New York and Miami. Epstein and MC2 denied they had any business relationship, but in a sworn statement in 2010, MC2’s former bookkeeper, Maritza Vasquez, said Epstein had guaranteed a $1m line of credit for the company and directly paid for the visas of models brought to the US to work for it.

Vasquez said Brunel and models as young as 13 lived in apartments controlled by Epstein on East 66th Street in Manhattan. Epstein didn’t charge rent, but Brunel billed the models $1,000 a month, Vasquez said. Virginia Roberts Giuffre, one of Epstein’s accusers, alleged in a 2014 court filing that the system was a cover for sex trafficking. Brunel “would offer the girls ‘modelling’ jobs”, the document read. “Many of the girls came from poor countries or impoverished backgrounds, and he lured them in with a promise of making good money.” Roberts Giuffre also alleges that she herself was made by Epstein to have sex with Brunel.

In 2006, the authorities caught up with Epstein and arrested him in Florida. He spent just 13 months in a Florida jail after pleading guilty to procuring an underage girl for prostitution. Brunel visited Epstein in jail no fewer than 67 times.

Brunel continued to operate MC2 in Miami until 2019. He led MC2 in New York until 2017, when he is reported to have sold the assets to help create two new boutique agencies, which are still running. Both deny any connection to Brunel.

In 1991, three years after the 60 Minutes exposé, Dutch model Thysia Huisman arrived in Paris, aged 18. An only child whose mother had died when she was five, she had been scouted in a Belgian club by a model agency in Brussels run by a female friend of Brunel’s. Brunel invited her to work for him at Karin and live at his Paris apartment. Huisman hadn’t heard about the CBS programme or its allegations, but nonetheless felt uneasy. However, the agent from Brussels told her that only “special girls he saw potential in” were given this opportunity, and that Brunel would take care of her.

One evening in September 1991, having already attended a number of Brunel’s dinners and parties, she accepted a drink that Brunel mixed for her. She describes feeling “paralysed”. In a previous Guardian interview, she said: “I felt him – this is difficult – between my legs. Pushing.” Huisman said the rest was a blur. She woke the next morning in a kimono that wasn’t hers, with soreness on her inner thighs. She gathered her things and fled. Her modelling work never recovered and she embarked on a career in television, always behind the camera.

Huisman is convinced that the female agent from Brussels knew about Brunel’s reputation before she went to Paris. “Everybody in the industry knew,” she says now. “That is still the thing that pisses me off the most.” Huisman says that four years ago she confronted the agent. She says she told her over the phone that she was mistreated by Brunel but was told that Brunel was “too sweet to do such a thing”.

Zoë Brock, a 17-year-old model from New Zealand, was in Paris at around the same time. She tells me: “I was a cheeky, fun-loving, adventurous and sassy kid – kid being the operative word.” She hadn’t heard about the CBS broadcast either, and her mother was reassured by her agent that she would be safe at Brunel’s home.

One night he called her into his bedroom, offered her cocaine and told her that “one of these days” they would have sex, she says. She took the cocaine but avoided him after that. However, she was soon told she could no longer stay at Brunel’s apartment, which Brock believes was punishment for refusing his advances.

In February 1996, 17-year-old schoolgirl Leandra McPartlan-Karol was invited to Paris to work for Brunel at Karin. She had already been scouted, aged 15, at the local fair in Tulsa, Oklahoma. She enjoyed school and was a flag-twirler in the marching band. She was in advanced maths and English classes, and loved chemistry and poetry. Before her modelling career started taking off, she had imagined a career trading stocks or as a chemist working on medicines or vaccines. But by 17, she was in demand in the US modelling industry, doing shoots for YM, Seventeen and Mademoiselle magazines. She was also photographed by David LaChapelle for Allure and Details. She had offers of further work in the US, but breaking into the European market seemed more exciting.

Unlike Huisman and Brock, McPartlan-Karol’s parents had heard about the CBS show and its allegations against Brunel, and expressed their nervousness. However, to allay their concerns, Karin flew a female scout to see her family. “She assured my parents that nothing like that was going on any more,” says McPartlan-Karol. Her parents agreed it would be safe for her to go. So she graduated high school early and made arrangements to fly to Paris.

They were told that the models’ accommodation was being repaired, so she would stay in Brunel’s apartment while he was away scouting. But when she arrived, he was there “and he’d been on one of his notorious, three-day coke binges”, she says now. After that, there were several dinner parties at the apartment. McPartlan-Karol says it was at one of these events that Brunel raped her the first time. “We were all hanging out in his living room and having drinks, and the next thing I knew I was just blacked out,” she says. “I was in and out through the rape … I just remember him being on top of me … like on my chest, forcing his penis in my mouth. That’s basically all I remember.” McPartlan-Karol attributes her blurry recollection to being in shock. She says she had slept with her high-school boyfriend, “but I didn’t really have much experience in anything, so it was all pretty new to me”.

Soon afterwards, she had the opportunity to model in New York. However, when Brunel found out, he locked her in her room: “He basically kidnapped me for three days because he didn’t want me to leave Paris.” She says Brunel’s maid would bring meals to the door. “My dad had to get on the phone with Jean-Luc and my agent in Oklahoma, and they had to negotiate my release.” McPartlan-Karol says she was too embarrassed to tell her parents about the rape. She said Brunel allowed her to leave on condition that she return to Paris to continue modelling for Karin afterwards. This time, she could live in the models’ apartment, not with Brunel.

Back in Paris, she “compartmentalised” the rape and focused on her work. Staff at Karin invited her to dinners and parties with “a bunch of older, wealthy men”, most of which Brunel did not attend. Cocaine flowed freely, she says, and she began taking it socially. When she did bump into him “it was very kind of casual and pally and, you know, just making me feel really comfortable”. One night she was at an agency dinner at Barfly, a popular bar-restaurant, and Brunel was there. “I don’t remember if we all left together, but I remember him driving me around in one of his vintage Ferraris back to his place,” she says. “I went upstairs to watch a movie with Jean-Luc and I was laying on my stomach. He was doing a lot of cocaine and I think I did a line with him, but it was getting late and I was kind of ready to go.” But Brunel started massaging her back, she says, “and that’s when he pinned me down and raped me anally”.

Speaking from the home she now shares with her film producer husband and four-year-old son in Hollywood, McPartlan-Karol tells me: “There was always that shame that it happened that second time, that I let it happen or was responsible for it.” Even now she tries to explain to me why she went to his apartment, saying: “We had been doing cocaine so I’m sure I was not making the best choices.” She says her cocaine use had become a coping mechanism. When she returned to the US and a family member found the drug in her bag, she says, she stopped taking it.

But despite McPartlan-Karol’s feelings of guilt, she didn’t want other models to go through what she had, and told her American agents. Among them was her so-called mother agent – the term used to describe the first agent a model works with, who develops their connections to the rest of the industry – in Oklahoma. Speaking to me now on the condition of anonymity, the agent confirms details of McPartlan-Karol’s story. “I think it was a Sunday, so it was quiet in the agency, and she came in and told me the whole story,” he says.

Having worked with McPartlan-Karol “since she was a kid” and got to know her family, the agent now feels he “let her down”. He decided to speak to Karin and confronted the female scout who had flown to the US and reassured McPartlan-Karol’s family she would be safe. They met in the lobby of a hotel in Tulsa, he says, and discussed McPartlan-Karol’s case until the early hours of the morning. He suggested McPartlan-Karol might consider going public, and raised the possibility of Brunel compensating the model. But he says the scout “made it very clear that Brunel had a relationship with the Russian mob”. He says: “I remember her saying, ‘If you don’t let this go, you will just disappear. That will be the end of it … you’ll just be gone.”

It’s not known if Brunel really did have mafia connections, but other sources who knew or worked with him say they suspected as much. Not long after the meeting, the Oklahoma agent left the industry. He says he is still scared of people linked to Brunel: “These people are way out of my league.” He adds, “I placed a lot of girls, but Leandra had the potential to be absolutely amazing, and that’s what’s so sad.”

Word of McPartlan-Karol’s allegations also got back to her agent in New York. From that point on, she says, “my career trajectory changed”. She can’t be sure her allegations were the reason her agent dropped her, “but back then, once you came forward about stuff like that, you were kind of damaged goods … they didn’t want to deal with it”.

In the mid-2000s she found out via social media that another of her former US agencies, based in Texas, was still sending models to work for Brunel, even though it had knowledge of her allegations. “It’s maddening,” she says. “I just couldn’t understand why you would put another young girl in that situation. There were so many people who were complicit.”

In the years since her experiences with Brunel, McPartlan-Karol says she has battled anxiety and depression. When she learned last year of the criminal case against him, and that at least 10 other women had come forward (including one with an allegation from as recently as 2000), she considered reporting her story. Brunel’s suicide came just as she was about to contact Anne-Claire Lejeune, a lawyer in Paris representing several of his accusers.

Brunel’s legal team said in a statement at the time: “His distress was that of a man of 75 years old caught up in a media-legal system that we should be questioning. Jean-Luc Brunel never stopped claiming his innocence and had made many efforts to prove it. His decision [to end his life] was not driven by guilt but by a deep sense of injustice.”

When news of his death reached his victims, they tell me they felt a mixture of dismay and disappointment. At the time, Huisman, who now lives in Amsterdam with her boyfriend and their son, and has written a book, Close-up, about her experiences in Paris, said she was disappointed that she wouldn’t be able to “look him in the eye in court”. Now, having had more time to process it, she tells me: “He died behind bars, and why? Because we used our right to come forward and we used our voices, and I hope it sends a message.” Brock agrees she is “happy he’s gone” and can no longer hurt any more women. McPartlan-Karol, now a full-time mother who volunteers with underserved communities in LA, hopes there’s a possibility for change in the industry: “Before, it was just like screaming into a void.”

Sign up to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly highlights

While the case against Brunel is now unlikely to go to court, a source close to the investigation tells me that the judge is in “no rush” to close the case, and is keen to identify other suspects or co-conspirators. Soerensen, now a web developer and a mother of four, says: “It just horrifies me to know in my heart that someone else is out there doing the exact same thing.”

In the months before Brunel died, Marianne Shine was filmed by the Sky documentary-makers giving her witness testimony over the phone to lawyer Lejeune, sitting on the sofa next to her 90-year-old mother, who was hearing her daughter’s story for the first time. She says in the series that Brunel’s death had left her with “a sense of feeling cheated at the last minute”. Now she tells me: “Jean-Luc Brunel’s death did not take away my hope. In fact, it’s fuelled it.” She adds: “I realised that this was much bigger than what happened to me … it became this big network, this boys’ club.”

Shine is keenly watching the criminal investigation into Gérald Marie. At least 14 women have testified, including supermodel Carré Otis. But in contrast to the Brunel case, none of the women’s allegations fall within France’s 30-year statute of limitations; unless a more recent one emerges, Marie will not be charged. “I think the pressure cooker is really rising,” says Shine. “He needs to be accountable for the decades-long abuse that he’s rained down on these women.”

Marie’s lawyer says he “categorically denies” the accusations against him, which “date back more than 40 years”, adding: “The complainants are attempting to conflate Jean-Luc Brunel, now deceased, with Gérald Marie. They therefore intend to frame my client as a scapegoat for a system, for an era, that is now over. However, in France, one does not condemn a system; one condemns a person, provided that it is proven that he or she has committed an offence. This proof is sorely lacking in this case.”

Shine, now quietly determined, says: “For many years, I was quiet. But I’m not any more … If you don’t step forward and talk about it, it’s going to continue to happen.”

Listen to Lucy Osborne and Marianne Shine discuss how the truth about Jean-Luc Brunel came to light on the Guardian’s daily podcast Today in Focus available from 31 May. Scouting for Girls: Fashion’s Darkest Secret launches on Sky Documentaries and streaming service Now on 24 June.

In the UK, Rape Crisis offers support for rape and sexual abuse on 0808 802 9999 in England and Wales, 0808 801 0302 in Scotland, or 0800 0246 991 in Northern Ireland. In the US, Rainn offers support on 800-656-4673. In Australia, support is available at 1800Respect (1800 737 732). Other international helplines can be found at ibiblio.org/rcip/internl.html