You realized it when you smelled it.

That overpowering musky cologne would hit your nasal cavities first, the bottled-up scent of the preferred man you experienced a top secret crush on. And then you’d hear it: techno club beats, blasting so loud you could truly feel the bass reverberate in your chest. And eventually, you’d see it: Two university-age shirtless white guys, all visible abdominal muscles and very easily swoopy hair, flanking either facet of the entrance.

Just walking by an Abercrombie & Fitch, the generically whitebred, preppy shopping mall chain shop of millennial nightmares, was an working experience of sensory overload.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, just going for walks by an Abercrombie & Fitch, the generically white-bread, preppy chain retailer of millennial nightmares, was an encounter in sensory overload. 20 a long time later, the memory is continue to seared into my brain, right alongside the Sbarro pizza my buddies and I would take in at the mall food court after a lengthy Saturday afternoon of browsing and chilling.

The exclusionary mother nature of Abercrombie was generally strongly implied, but harder to grasp clearly. Especially when you were being, like me, in center school and high college — arguably the a long time when lots of youngsters want very little more than to easily mix in — for the duration of the brand’s cultural zenith. But a new Netflix documentary, “White Very hot: The Increase and Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch,” describes explicitly what a lot of of the young people purchasing up A&F’s generic polo shirts and small-increase denim pants knew implicitly: The clothes arrived secondary to the vibe. Since what Abercrombie was providing in its heyday was a culture — the awesome crowd. And “cool” had guardrails. It was white. It was slender. It was affluent. It experienced highly obvious ab muscles. It was wearing a graphic tee with a moose head printed on it.

“White Scorching,” directed by Alison Klayman, traces the way in which Abercrombie’s distinct-eyed exclusionary branding facilitated equally its precipitous increase and its top economic downturn from mainstream relevance. A person former staff described the company’s using the services of methods, cost and imagery as representative of “the worst elements of American record.”

Abercrombie & Fitch as millennials know it seriously commenced with Les Wexner. (Sure, the very same Les Wexner who reportedly helped aid Jeffrey Epstein’s increase). Wexner, founder of L Makes, acquired Abercrombie & Fitch, then a failing elite sportsmen manufacturer that catered to the likes of Teddy Roosevelt, in 1988. He soon understood that revamping the company for its historical client — middle-aged athletic white dudes — wasn’t heading to function. So in 1992, he brought in Mike Jeffries as CEO.

Jeffries is the one who manufactured A&F into an arbiter of amazing, with stores whose home windows had been blocked by shutters, and exactly where hardbodied male models “guarded” the entrances. Jeffries leaned on acclaimed photographer Bruce Weber to generate the brand’s signature aesthetic — black and white, preppy Americana, centered on the fifty percent-bare male kind. (Weber has considering that confronted allegations of sexual assault and harassment from versions, all of which he has denied.)

Jeffries obsessively monitored the attractiveness of revenue associates, and gave keep managers handbooks with racist guidelines about look like “a neatly combed, appealing, traditional hairstyle” is satisfactory, but “dreadlocks are unacceptable for adult males and ladies.” Underneath Jeffries’ stewardship, the company’s seemingly discriminatory choosing practices spurred a course-motion lawsuit in 2003. Decades later, when an A&F retail outlet refused to use a younger Muslim girl since she wore a hijab, the firm fought the situation all the way up to the Supreme Court, which eventually dominated towards Abercrombie, 8-1.

The A&F leader obsessively monitored the attractiveness of gross sales associates, and gave shop administrators handbooks with racist policies about visual appeal.

Less than Jeffries’ management, it is tough to overstate how absolutely the Abercrombie aesthetic manufactured its way into suburban colleges across the place. (Primarily in white, affluent communities.) For these of a specified age and socioeconomic class, even if you never ever shopped at a person of its aggressively perfumed shops, you possibly have inner thoughts about the brand. Probably A&F was aspirational for you. Maybe it was corny. Possibly it was just stupidly overpriced. Probably it was scary. Either you ended up in, or you ended up out — just the way Jeffries appreciated it.

“Fashion is advertising us belonging, self esteem, cool, intercourse attractiveness,” Washington Post critic-at-huge Robin Givhan says in “White Hot.” “In some methods, the incredibly very last detail that it’s providing is actual clothes.”

In that feeling, Abercrombie wasn’t just offering the masses racist, xenophobic graphic tees. It was promoting reassurance to insecure teens that if they could fit their bodies into these outfits, and see their faces in the faces (and abdomens) of the styles plastered on the store partitions, then they were going to be all right. Maybe better than all right. To be decided on by Abercrombie — to perform in its shops or design its apparel — or to effortlessly suit into Abercrombie (the brand name famously did not make measurements greater than “substantial”) was synonymous with desirability. And what teen does not crave the reassurance that they are needed?

And Jeffries produced no bones about his mission to sector exclusivity. “In each and every college there are the awesome and well-liked kids, and then there are the not-so-cool kids,” Jeffries instructed reporter Benoit Denizet-Lewis in 2006. “Candidly, we go following the awesome kids. We go immediately after the eye-catching all-American kid with a great mind-set and a lot of buddies. A great deal of persons do not belong [in our clothes], and they simply cannot belong. Are we exclusionary? Completely.”

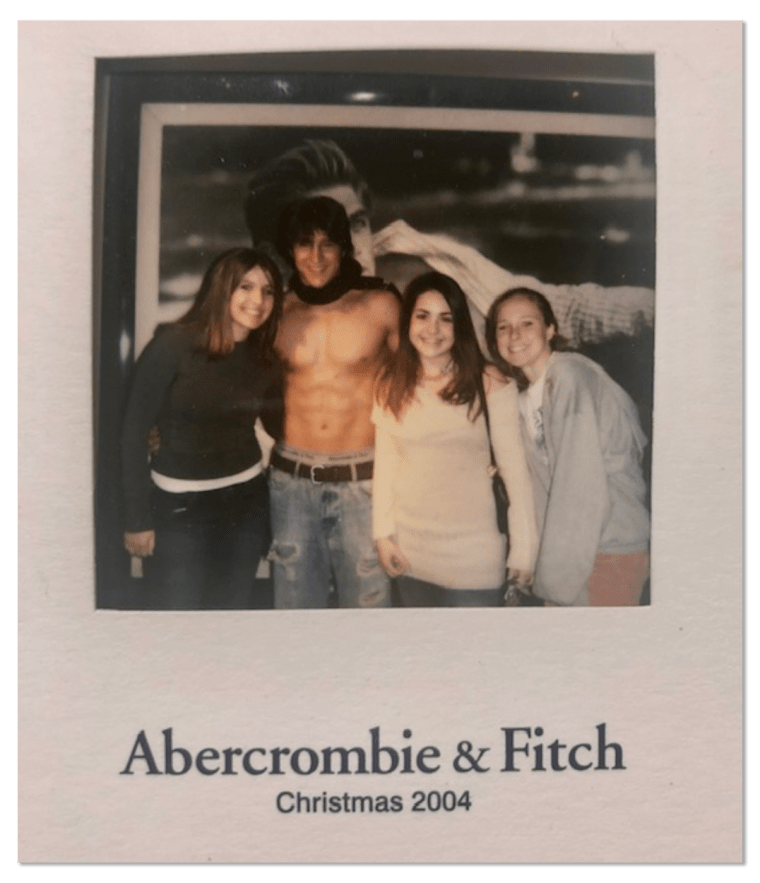

Even with my slim privilege and white privilege, I always understood implicitly that I was not the sort of woman who would at any time be recruited to be an Abercrombie revenue affiliate. I was way too Jewish and too brunette and a very little way too awkward in my freshly pubescent overall body. I was additional of an American Eagle gal — it was a minimal more cost-effective and a tiny significantly less scary — but that did not cease me from perusing the A&F cabinets and jokingly getting a Christmas polaroid with one particular of the regional shirtless products. (The advertising budgets these retailers ought to have experienced. Unquestionably wild!) In the early aughts, so several young people seemed to exist in relation to the Abercombie perfect, an ideal that experienced no qualms about expressing outright disgust for whole segments of its prospective shopper foundation.

To be honest, Abercombie did not exist in a vacuum. This was an period in which younger women’s bodies were not only regarded fair activity for intake, but also for in depth, excruciating critique. (This was, soon after all, the period of Jessica Simpson’s “mom jeans” gaffe and the constant stream of degrading tabloid headlines about a complete plethora of youthful feminine stars.) The micro miniskirts and 3-inch rise jeans that have been so pretty on development seemed built to exhibit the torsos of women of all ages and girls, and so open up them up to outside the house evaluation and normally scorn.

In fact, what “White Hot” finally elucidates is that Abercrombie did not do nearly anything specially remarkable. It simply just capitalized on a depressing reality of American culture that has not fundamentally changed: It’s racist, it is sexist and it is fatphobic.

As Givhan place it, Abercombie’s meteoric increase is actually “an extraordinary indictment of where our tradition was, just 10 a long time ago. It was a lifestyle that enthusiastically embraced a virtually all form of WASPy eyesight of the entire world. It was a society that defined natural beauty as skinny and white and youthful. And it was a lifestyle that was delighted to exclude individuals.”

No 1 waved a magic wand and preset those people factors in the very last ten years or two. But what has modified is our collective willingness to tolerate these types of overt rubbish. In the decades considering the fact that Abercrombie’s cultural peak, social media established the skill for people to give suggestions publicly and amplify it tenfold. The body good motion obtained steam and confirmed several trend models that resisting inclusive sizing meant leaving massive income on the table. Individuals in marginalized bodies simply have extra channels to demand from customers greater from the brand names that make funds off of them, or in relation to them.

In 2014, decades after the brand’s “cool” aspect experienced started to wane, Jeffries stepped down as CEO. Obviously, he obtained a large exit offer, and a white lady, Fran Horowitz, was brought in to clean up up the mess.

Since then, Abercrombie has in fact launched a rebrand. Their stores are no extended doused in the signature fragrance “Fierce.” The illustrations or photos on the brand’s web page and in suppliers include Black faces and other folks of shade, as very well as bodies of much more sizes and gender expressions. The apparel are significantly less aspirational, and additional sensible, elegant fundamental principles for the really millennials who the moment felt excluded.

As micro minis and reduced-increase denims the moment yet again start out to dominate the runways and outlets, I can sense my stress and anxiety concentrations rising. Racism, sexism and fatphobia can all be propagated by means of manner just wonderful with or with out Abercrombie & Fitch. Large-finish makes are even now partaking in tone-deaf cultural appropriation. Excess fat men and women are even now combating for correct inclusivity from the style business, not just a handful of measurement-16 models in commercials. Attire makes are even now failing to do additional than give lip services to gender equity.

But for now, when I wander by an Abercrombie at 1 of the country’s remaining malls or scroll as a result of their application on my mobile phone, I do not see an aspirational way of life. I blessedly just see some clothing.